FDA Device Recalls: A Primer for Medical Device Research & Development Leaders

- Posted by

- On May 4, 2020

When medical device Research & Development groups face the potential for a recall, it’s an all-hands-on-deck situation. Smart R&D leaders must equip themselves ahead of time in order to lead effectively during recalls. Recalls are necessary and healthy because they protect patients and avoid unnecessary harm, but recalls can also be an expensive and time-consuming process for medical device manufacturers. Recalls create an especially intense and high-pressure situation for R&D leaders. This article summarizes the current recall environment, describes actions that may lead to a recall, and outlines actions your organization should take to be prepared in the event a recall is required.

Recent Device Recall Trends

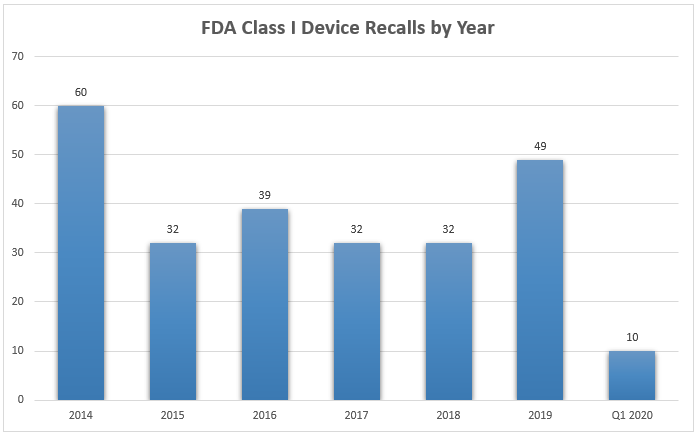

Class I medical device recalls jumped significantly in 2019, reaching their highest level since 2014 with a total of 49 Class I recalls1. Statistics show that the reasons for medical device recalls have evolved over the last decade. While “device design” was the predominant cause of recalls between 2010 and 2014, software was the #1 reason for a recall between 2015 and 2018.4 In 2018, the top 3 causes of recalls were: 1) software, 2) mislabeling, and 3) quality issues.3

Technology advancements and device complexity are both partially responsible for the increase in recalls, but increased oversight is an equally valid reason. The FDA expanded the number of annual device inspections by 46% between 2007 and 2017. The FDA also increased the number of foreign device inspections by 246% during the same period.2

Anatomy of a Medical Device Recall

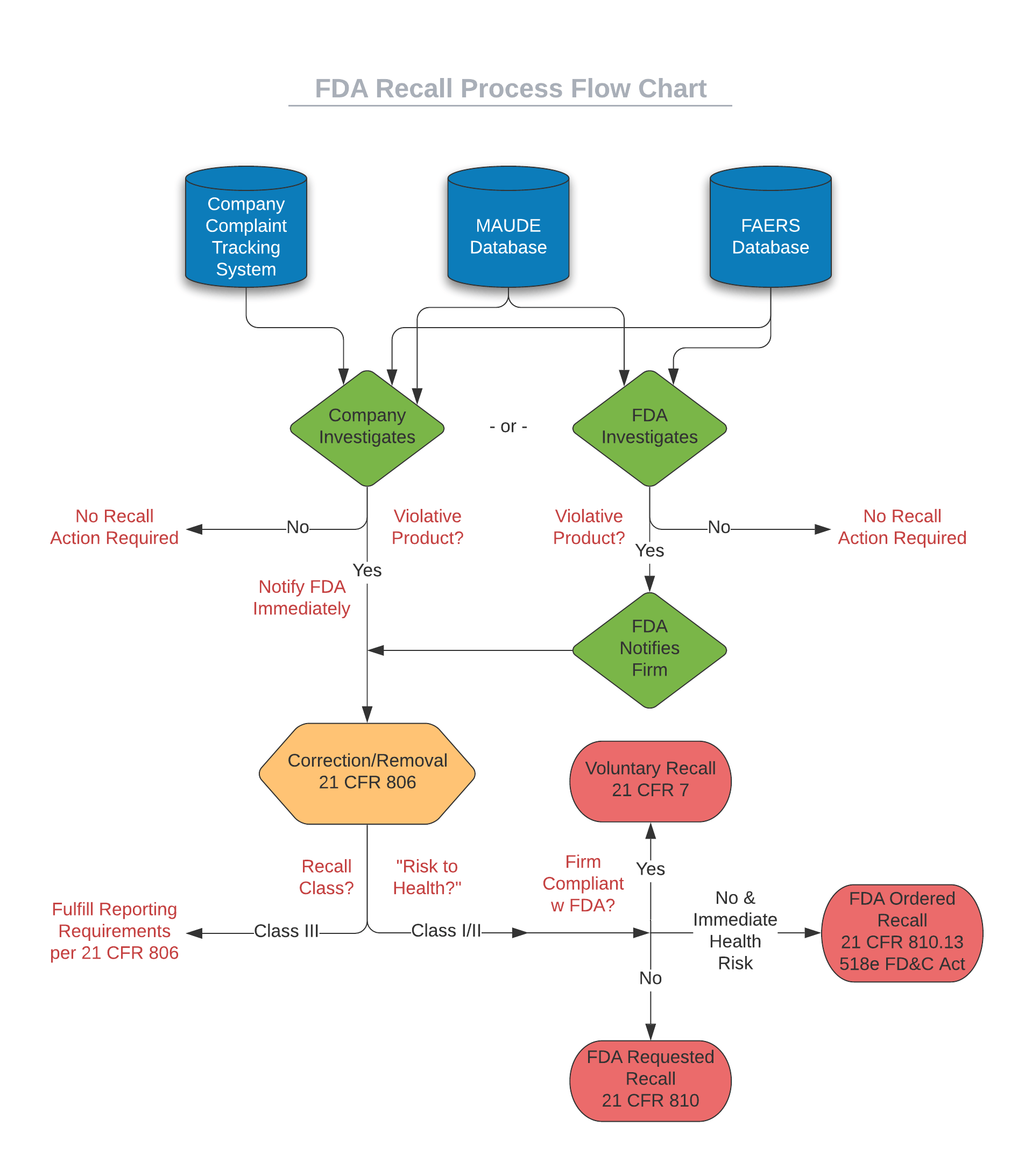

Medical device recalls can begin at either a device manufacturer (self-initiated) or at the FDA, depending on where the first signs of trouble are identified. Internally, a manufacturer’s complaint handling system could signal issues in the field, or a quality team may notice reports listed in the FDA Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) and FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) databases. The FDA monitors those same databases, and they will conduct a health hazard evaluation if they believe a product may be violative – a product that is in violation of applicable regulatory and statutory laws. As shown in the flowchart below, two different paths may lead to a recall – a company self-reported path or an FDA-identified path.

Regardless of which path the recall investigation starts down, your firm’s quality and engineering teams will have their focus quickly diverted to efforts such as investigating adverse event reports, conducting testing to recreate hazards, and analyzing manufacturing records. The goal of the investigation is to determine whether the device is violative or poses a “risk to health” for patients. Per the FDA, “risk to health” means (1) A reasonable probability that use of, or exposure to, the product will cause serious adverse health consequences or death; or (2) That use of, or exposure to, the product may cause temporary or medically reversible adverse health consequences, or an outcome where the probability of serious adverse health consequences is remote. If the product is determined to be violative, actions for correction or removal are required, and the process is initiated according to the guidelines outlined in 21 CFR 806 and potentially 21 CFR 7 – more on that later.

If the FDA conducts a health hazard evaluation and determines a violative product exists before your firm reaching that conclusion on its own, the FDA will notify your organization and request attention to the matter. Regardless of whether your firm initiates the action (firm-initiated) or if the FDA brings the concern to your organization first, the actions will be considered voluntary unless your company does not cooperate or take action upon notification from the FDA. Only in the rare case of a manufacturer failing to act on the FDA’s request will the FDA resort to issuing a mandatory recall order.

Recalls come in three classifications – Class I/II/III – with Class I being most serious and Class III being unlikely to cause adverse health effects.

The FDA will assign the classification to the recall as part of the health hazard evaluation process. The classification will have a bearing on the mandatory next steps. The primary difference between recall classes is whether a “risk to health” was found. If the risk to health is nonexistent, the recall will be classified as Class III, and your firm will be required to fulfill the requirements for reporting as outlined in 21 CFR 806 but will not need to take further action. If, on the other hand, the device has been determined to pose a “risk to health,” the recall will be classified as Class I or II, and more complete recall actions will need to be taken. Class I and II are differentiated by severity of risk to health. The recall strategy developed by your company (and approved by the FDA) will be driven by the severity of the hazard, the recall class, and the extent of distribution of the device. The recall strategy may address the following:

- Depth of recall – consumer level, retail level, wholesale level

- Public warning – general public (national/local media), trade publications

- Effectiveness checks – verify notification and action to the appropriate depth of recall

Your organization will work closely with the FDA as the recall progresses, and devices are removed or corrected to address the issue.

How Can You Be Ready?

The FDA recommends the following steps to minimize the disruption that a recall can create:

- Prepare and maintain a contingency plan to use for initiating and effecting a recall per 21 CFR 7.

- Utilize sufficient tracking of regulated products to make positive lot identification easier and to help facilitate the effective recall of all affected product.

- Maintain tight distribution records such that all violative product can be located easily. Ensure that such records are maintained for a sufficient period to exceed shelf life and expected product life and in accordance with any other applicable regulations related to records retention.

- In addition to the above FDA recommendations, we recommend cultivating the ability to scale up engineering resources for surprise demands (such as a recall). Establishing a basic partnership ahead of a surge demand situation is one way to make sure help is available quickly when you need it.

Even with advanced planning, a potential recall is a significant event that is a challenge for any R&D leader and organization to handle. The opportunity cost of diverting human capital to handle a recall could be sizeable and impact long-term new product development plans. Having the ability to quickly add strategic, expert resources to address your firm’s needs in the event of a recall could be a valuable option.

Engenious Design has a team with experience designing dozens of medical devices. We have all the design and engineering disciplines under one roof, including electrical, mechanical, systems, and embedded software engineers, project managers, human factors and regulatory experts. Our “fold into your team” style of work facilitates close collaboration and could potentially help alleviate bottlenecks in your R&D team.

Sources:

1 “Medical Device Recalls” https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-safety/medical-device-recalls

2 “Medical Device Enforcement and Quality Report”, November 2018. https://www.fda.gov/media/118501/download

3 “Q4 2018 Recall Index”, Stericycle Expert Solutions https://www.stericycleexpertsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/ExpertSolutions-RecallIndex-Q42018-web.pdf

4 “What’s Behind Medtech’s Recall Epidemic? Part 1: Device Design”, Medical Device and Diagnostic Industry https://www.mddionline.com/what%E2%80%99s-behind-medtech%E2%80%99s-recall-epidemic-part-1-device-design